The Two Towers by J.R.R Tolkien (Harper Collins 1991, 2007) pp. 874-878

As Faramir guides Frodo and Sam towards Henneth Annûn he speaks thoughts aloud that, perhaps, he has not shared with anyone else. We have already met his brother, Boromir and know that he was a man of a very different spirit. Later we will meet his father, Denethor, and we will learn that Faramir could not have shared his heart with him. Denethor, as we will learn, discerned much of what lay in his younger son’s heart and laid the blame for this at Gandalf’s door. There is little doubt that Gandalf was a great influence upon Faramir. As with Frodo in the Shire and Aragorn in Rivendell he found out young men and taught them, but they needed to be young men of the right spirit. That Frodo, Aragorn and Faramir all emerged at exactly the same time must have been the cause of great delight for one who came to teach, as Gandalf had done. For it was through teaching, not through the exercise of power, that Gandalf came to change the world.

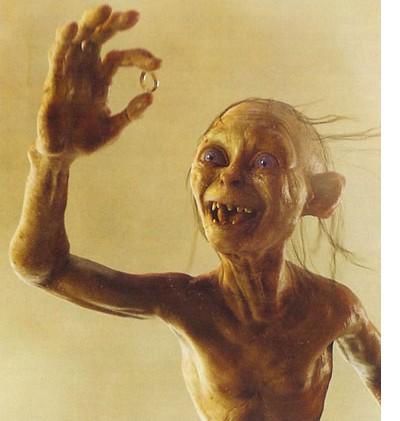

John Howe imagines Gandalf, alone and vulnerable, a pilgrim going from one place to another in order to teach or to give counsel.

Last week we learned that Faramir too had no desire for power if it came from an evil source. He has some sense of the nature of Isildur’s Bane even though he does not yet know that it is the Ring of Power that Sauron made to enable him to rule all things. Now we learn what Faramir believes about power itself and the power of his own country.

“For myself,” said Faramir, “I would see the White Tree in flower again in the courts of the kings, and the Silver Crown return, and Minas Tirith in peace: Minas Arnor again as of old, full of light, high and fair, beautiful as a queen among other queens: not a mistress of many slaves, nay, not even a kind mistress of willing slaves.”

The White Tree of Gondor in the Court of the Kings in Minas Tirith. A symbol of Gondor’s fallen state but also its rootedness in the most ancient wisdom.

Tolkien wrote these words towards the end of an age in which his own country, Great Britain, had ruled over an empire, greater in area and in population, than any that had existed before it. By the time he died, in 1973, most of this empire had gone. One particular empire no longer existed but the idea of empire was as strong as ever. The British Empire had been one of many that had existed throughout world history and after its decline and fall it has not been the idea of empire that has disappeared, merely a particular expression of that idea.

As you can see, I have used the word, decline, in speaking of this history and that is how it is usually understood. For about a century after the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, Britain was the greatest world power but the story since then has been one of decline. The assumption made here is that the exercise of power, if you have it, is how things are. And when power is spoken of it is military power that we are speaking about. We remember that when Boromir spoke at the Council of Elrond he made reference to the counsel that his host might offer in a somewhat dismissive manner. This “counsel” was all that he expected. It was only when discussion turned to the Ring that he became really interested because he understood this kind of power.

Faramir understood power in a very different way. For him power was meant to be exercised for the good of all; “a queen among other queens”. And the power of Gondor was to be first and foremost power in wisdom, of goodness, beauty and truth. To achieve power in which wisdom was absent was of no value at all. It was a thing to be left by the side of the highway, a piece of rubbish that we notice, if at all, and then pass by.

We might ponder how the history of the Americas, or of Africa, might have been different if Europeans had come, not to conquer but the mutual exchange of teaching and learning. We might wonder in what way the history of the world might have been different. Next week we will think about what part the ability to wage war has to play in such a world. Faramir recognises that this ability will always be necessary in a world in which some will seek dominance over others. After all, he is a soldier himself, and a very good one. But his dream is not the one that Boromir spoke of to Frodo when he tried to take the Ring. He does not wish others to flock to his banner because of his martial prowess. Faramir wishes to be a great teacher. Gandalf, not Saruman or Sauron, is his model.

Where does the power of Elrond lie?