The Two Towers by J.R.R Tolkien (Harper Collins 1991, 2007) pp. 607-611

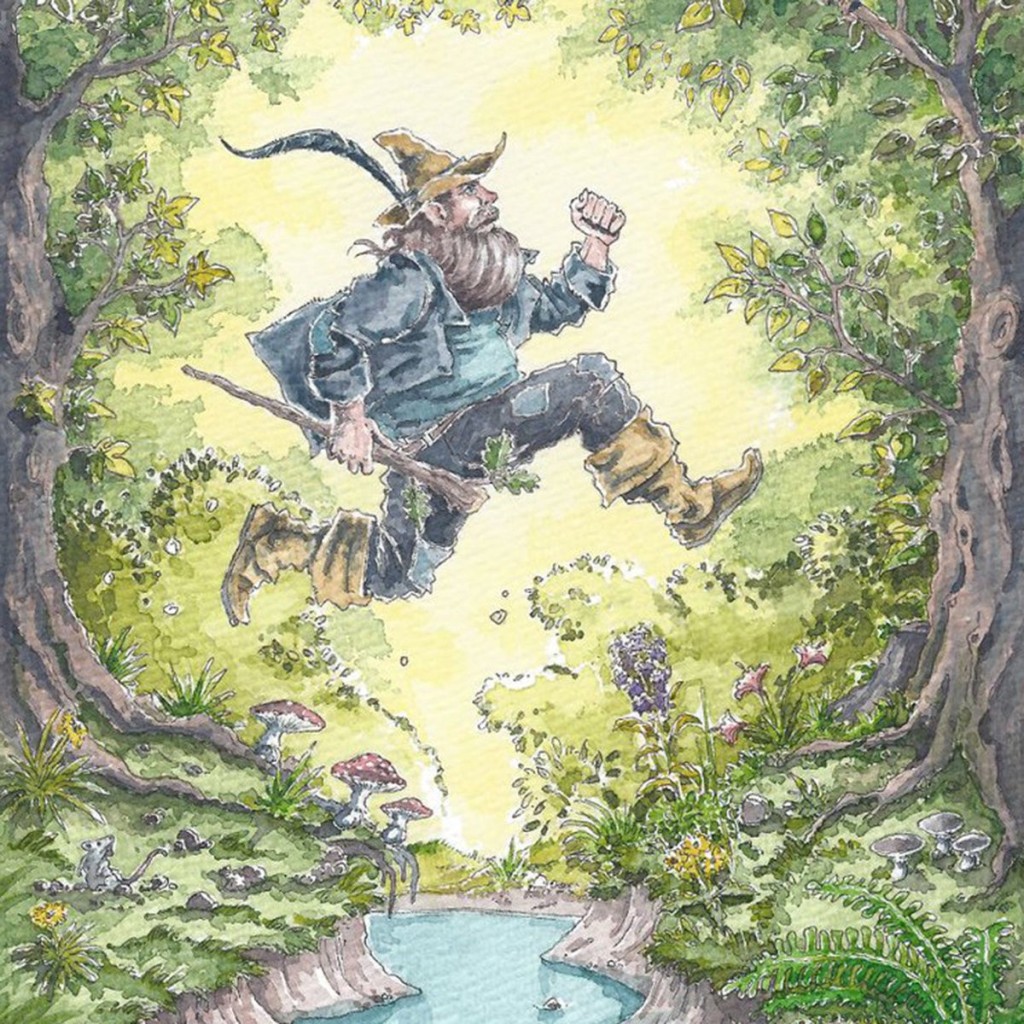

Carefully but firmly holding Merry and Pippin in the crooks of his arms Treebeard makes his way through the Forest of Fangorn. The hobbits have had plenty of experience of being carried in the past few days but the last one was by orcs, “seized like a sack” and crushed into their necks. Their arms were gripped like iron with orcs’ fingernails biting into their flesh. This is very different, soon Merry and Pippin begin to feel “safe and comfortable”, hobbit curiosity gets the better of Pippin and there is something he wants to know.

“Please, Treebeard,” he said, “could I ask you about something? Why did Celeborn warn us against your forest? He told us not to risk getting entangled in it.”

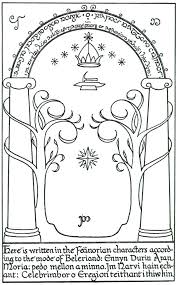

It is a theme that runs through The Lord of the Rings that its free peoples have become divided from one another so that there is a sense of hiddeness and wariness about each land in which strangers are treated with suspicion. So normal has this become that when Gandalf, who has worked harder than any to break down barriers between peoples, is confronted with the words pedo mellon a minna on the western doors of Moria he assumes that a secret password is required of him. In fact all he needs to do is to say the word, friend, mellon, and the doors open. This is a fact that I note was completely ignored in the recent Amazon dramatisation, The Rings of Power. We live in suspicious times once more and, like Gandalf, assume that doors will be closed against us. Even the stories that we tell tend to be of suspicion and wariness rather than friendship and openness.

Treebeard speaks of this as he ponders Celeborn’s own land, the Golden Wood, turning over Elven words as one might allow a fine wine to linger upon the tongue before swallowing it. Lothlórien too is a dangerous place, “and not for anyone just to enter in”. We might note that when Gandalf took Gollum prisoner it was to the realm of Thranduil that he took him and not Lothlórien. The secretness of that land needed to be preserved.

It is darkness that has divided the peoples of Middle-earth, darkness not as a welcome pause between periods of daylight in which rest can be taken and moonlight and starlight enjoyed for their own sake but as a thing of threat in which enemies might be hiding ready to do harm. Treebeard speaks of “the Great Darkness”, presumably referring to the time that followed the destruction of the Trees of Light in Valinor by Morgoth in the First Age, a time in which darkness did not merely mean an absence of light but had a quality of its own, the kind of hopelessness to which Dante refers in the motto that stands above the Gates of Hell in his Divine Comedy. It is this kind of darkness that entered parts of the realm of Fangorn just as it did in parts of The Old Forest near the Shire. Treebeard speaks of some trees in the forest especially in the valleys under the mountains that are “sound as a bell, and bad right through.”

The Ents have watched over the forest since time immemorial and they have tried to teach the trees about light, opening their hearts to it, softening those hearts. And they have tried to keep unwary folk away from danger. And it must surely be a fruit of their work that at the end of The Lord of the Rings Legolas takes Gimli upon a voyage of discovery through Fangorn that is a source of delight and wonder and not one of danger and threat. It is not just because of Sauron’s fall that the darkness has been lifted, the time for that has been much too brief, it is because through the work of the Ents that the forest is full of light. But perhaps Legolas and Gimli had the services of an Ent to guide them through the forest. We are not told. A guide such as Treebeard could take a guest into secret places safely, unfolding them to those who wish to take time to enjoy them. This would be a different way of getting to know a forest than to take a truck along a highway that has been driven through its heart like a sword thrust.