The Two Towers by J.R.R Tolkien (Harper Collins 1991, 2007) p. 787

I spent a pleasant evening with a friend in a pub recently (Thanks, Ben!) talking about The Lord of the Rings and we got to thinking about heroes and, more specifically, the kind of heroes that Tolkien’s hobbits are. We compared them to superheroes in, say, a Marvel comic or film. Now I was an avid reader of those comics as a boy and I am happy to say this with pride now with C.S Lewis’s thought in mind that he would rather see a boy reading a comic with pleasure than a classic novel because he thought he had to. I also fell in love with Narnia so I hope that would have pleased him too. I was fascinated by the characters of the heroes and their inner struggles just as much as their triumphs over evil. I was just starting to become aware of my own struggles and they gave me some comfort and the thought that I might be a hero too.

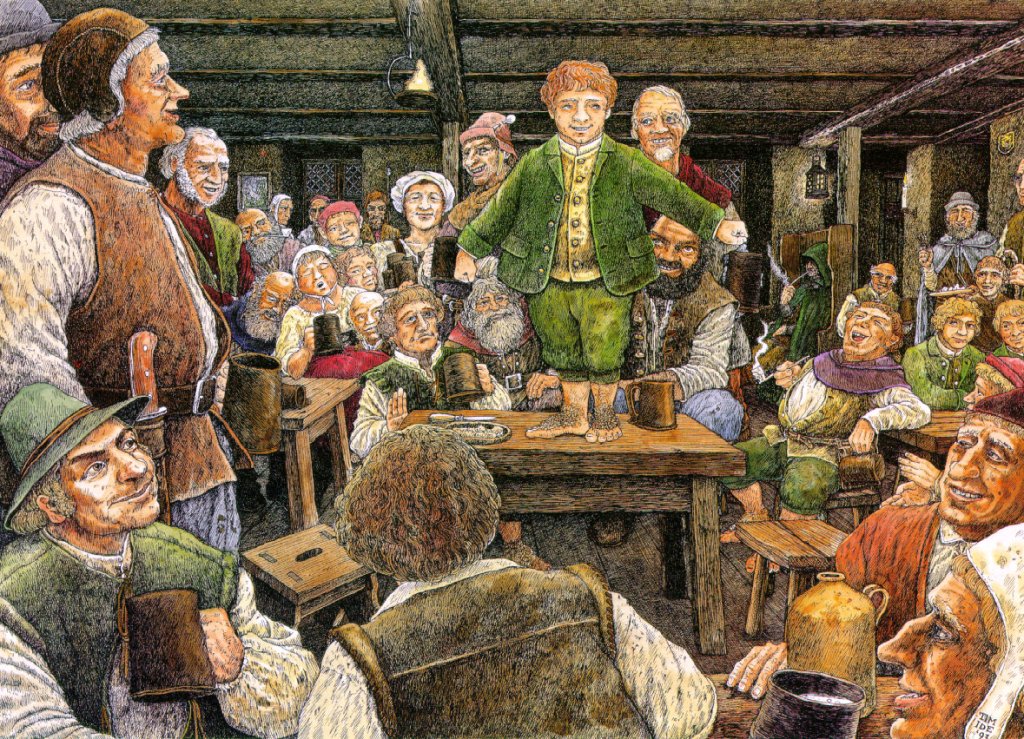

Heroes from Marvel Comics and Films

But we agreed that Tolkien created a different kind of hero in Frodo and Sam. In fact, as Tom Shippey has shown, he created the kind of hero that could only have been created in a 20th century story, the kind that would have experienced industrial warfare, as Tolkien and Lewis did on the Western Front of the First World War of 1914-18. And while in a Marvel story the hero comes to save the day while the rest of us run for cover or stand helplessly with our hands raised over our heads as the forces of evil destroy our city around us, Tolkien’s hobbits are more like us.

Yesterday I listened, deeply moved, to a news report that the French military attaché to the United Kingdom unexpectedly arrived at the hundredth birthday celebration of a veteran of the Normandy landings of June 1944 and presented him with France’s highest honour, the Legion d’honneur. I was moved by this because my father took part in those landings and, had he lived, would recently have celebrated his own hundredth birthday. I felt that my Dad was being honoured too. The old gentleman was interviewed on the radio and, speaking with admirable clarity, said that he did not feel that he deserved the award because, as he put it, “I was just there”. I think my father would have said the same thing. In fact the only story that he ever told us of the experience was that as he was going ashore on the Normandy beaches in his American built landing craft he noted that it had an ice-cream maker fitted and wondered what it was doing there. If any of my American readers know the answer please let me know in the comments below.

British soldiers coming ashore on the Normandy beaches in June 1944.

But that “I was just there” remark typifies Tom Shippey’s argument about the “heroes” of 20th century warfare. Whereas Lancelot, riding to rescue Guinevere from her captors, is a hero of romance, the veterans of the Normandy landings of 1944 were “just there”, doing their duty and trying to stay alive.

Tolkien gives us both kind of heroes in his story though he hardly ever used the word. In Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli, following the orcs of Isengard across the plains of Rohan in the hope of freeing Merry and Pippin from their captivity we have the kind of hero that Sir Thomas Malory would have recognised in his Morte D’Arthur. In Frodo and Sam trying to find a way down from the Emyn Muil to the livid marshes below we have something quite different. They are more like the men going ashore on the Normandy beaches in 1944. They just keep going. Or, at least, they try to.

But Frodo and Sam give a dignity to every person who has ever just kept on going, trying their best to do whatever good they can in their lives. I have had conversations with my daughters about this recently as they have looked in horror at evils in the world and have wondered what can be done. I have thought about it in reference to my own life as I have asked myself the question, “What use have I been?” And like Frodo and Sam, I won’t pretend that my story has been like Aragorn’s or Lancelot’s although there was a time when I wanted to be like that, but, whether I ever write it down or not, I will try to create my own Red Book in my head of what I have tried to do, of how I have tried to answer Gandalf’s principle that all any of us can do is “to decide what to do with the time that is given us”.

And not to give up.

Frodo and Sam just keeping going.